Instructions from the Spiritual Teacher

Since 2005, Babaji has been conducting an email correspondence course on the Yoga Sutras. Each class provides an opportunity for students to ask questions about the teachings and how to apply them in their lives. Great depth and diversity of practical spiritual knowledge and methods have been transmitted to the participants via this process.

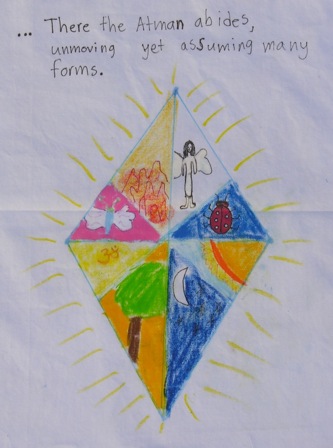

The following exchange is from lesson #16. The student’s question arose from the prior lesson wherein Babaji elucidated on Sutra 17 from chapter one, introducing meditation on the alambanas, the famous 24 Cosmic Principles of Sankhya philosophy. These alambanas include the five great elements, five subtle elements, the 10 senses of knowledge and action, mind, ego, intellect, and the Cosmic Mind.

STUDENT’S COMMENT: “While I have studied the lesson as hard as I could, I have not tried to actually meditate on the alambanas yet. Having followed a devotional practice with mantra for so long, I sincerely don’t know when or even how to add this type of concentration. It seems overwhelming to me even though it is presented sequentially and I just feel like a beginner again, which, of course, is not always a bad thing! It sounds as though it needs a ‘formal’ sitting, rather than just something you can contemplate throughout the day, at least at first. In addition to mantra, I do the Shinay Meditation which does include recognition of the basic elements, but does not include details like the evolutes. I am wondering if I can intensify the steps within that. It has been made clear that there are many more details that have to be left out because of our e-mail format and yet I realize how important it is to attempt some application of Sutra 17 since Babaji has said, ‘There is no jumping steps in Yoga. The grosser objects are to be contemplated first, their potencies realized, and each left behind (implemented/transcended) in turn once their nature has been understood.’”

STUDENT’S QUESTION: “Despite the advanced nature of what we are attempting, is there any practical advice to help me get started…. how can I include this in my established practice? For example, what should be going through my mind when I contemplate water and when would I include it in my practice? Would all the ‘results’ from each ‘object’ be the same, that everything is Brahman, that everything in maya is in motion and is fleeting, or is there a special energy that I would note for each object of contemplation?”

BABAJI: First, a time of formal sitting is enjoined upon all seekers. Yogis/Yoginis give much time to their art, just as others give to earthly pursuits. Therefore, in addition to one’s meditation with the mantra, and on the formless Reality, one must cut out some time to sit and practice, experiment even, with this newly presented form of meditation.

Now, as one exerts in the spiritual realm one will find that a part of this practice is really a filling in of blanks, or a taking of steps one jumped earlier. The Divine Mother path is essentially one of integration, and that is why it is superior and goes deeper into the transformative areas of spiritual endeavor. Knowledge, called tattva-jnana, and worship, called upasana-dhyan, and sadhana, called Yoga, are all combined in any good Shakta path. And the goal is Advaita, nonduality. What I am saying here, proposing to all, is that we cannot remain content with the early form of practice that the guru first presented, but must push onwards. The man pursuing earthly success does not remain content with a beginning salary, but strives for more, and must do so to cope with rising costs on all sides. Similarly, remaining content with an hour a day meditation period does not a yogi or yogini make. Nor does a reading of a few slokas, or a little ritual, or some occasional service to the poor, the sick, or the aged, etc. What I am getting at is that when you practice this form of yogic meditation, you will be filling in gaps in your understanding that all along have been keeping you from a vast and higher realization. Let me use an example:

Attachment to nature is deeply rooted in the soul; so is aversion. This is duality, and it exists as a limiting factor in the minds of living beings. We love water as we swim, but we hate it when we are drowning. We love the sun when we are sunbathing, but hate it when we get sunburned. Well, the alambana, called ksiti, or earth, has a real fascination for us. We love it as solid foundation under our feet, love to sink our hands into it, love to smell the various fragrances which emit from it, love to see all the plantlife that springs up from it. But we would hate to see it descending upon us in the form of hot ashes, or heading our way in the form of molten lava or a landslide. In short, we desire it and we fear it based upon a long-standing relationship that has, in part, helped fashion our subtle and hidden samskaras (mental impressions) around it.

This love/hate relationship, like all of its ilk, is restricting to the freedom-loving soul, the yogi. He would thus take earth up, whether in a handful, as an entire planet, or as the concept of solidity itself, and put it to rest, once for all. He thinks, “enough of base, debilitating love and of stark, crippling fear.” He would know, in fact, of the very Mind (Mahat) that formed worlds, and in order to do that he must free himself first of the duality around it and the alluring/threatening presence of it in his own mind. In other words, loving the earth while at the same time secretly fearing its negative side — its aging, impurities, degeneration, decay, destruction and the pain and suffering that proceed from it — is just not doing the job. Death too, as well as life, is present in the earth and all its concomitants.

Then, one may ask, how can Vivekananda, knowing this, write: “The shade of death, and immortality — both these are Your grace, O Mother Divine!” Because he, like any successful yogi, has taken up all the alambanas and seen them as they are; we have not done that yet. The yogi’s meditation upon them has been both undertaken and consummated with the one aim of neutralizing the dualities inherent in them. And these dualities exist in the mind-field. How is he going to dissolve them? One way is to step by step remove all the barriers (material principles and their stultifying presence) in the way of access to the mind. But as long as the mind is attracted to and averse to them, how successful will that attempt be?

Take up your handful of earth, then, or think in your mind about the transitoriness of the world of matter. Do both, but consummate the experiment, the study, by an apt conclusion and a resultant mental withdrawal. Says Ramakrishna, “There is no more unfortunate a person than that knowledgeable one who sees the world to be unreal, but still cannot give it up.” Your examination of all the alambanas will reveal that they are all insentient after all, and that you cannot mix the Soul with them. And the fact that you have attempted to do so for so long — sought, resisted, loved and hated the sun, the ocean, the earth, the air, and the atmospheres which caused us so much pleasure and pain — only resulted in bondage or, put another way, secured the loss of your rightful freedom. Further, to compound the problem, beings romanticize the entire process. Soon, as they mix indiscriminately with nature, mountains are sending messages, trees and forests are talking, the air is whispering secrets, and the oceans themselves are pulsating with life. What nonsense! Where there is life, there is death. Walk into those ocean waves “pulsating with life” here in Hawaii and you will soon be in a state of nonpulsation — no pulse. It is the Self, Atman, which truly lives. All else borrows its sense of life from That. And the borrowing is only a sense, a semblance; do not romanticize it and invite duality into your mind, later to suffer in confusion. By your meditation come to know that there is no lasting abidance or intelligent principle in objects. Thus Swami Vivekananda tells us here in the West:

There is but One,

seen by the ignorant as matter,

by the wise as God.

And the (unfortunate) history of civilization

is the progressive reading of Spirit into matter.

The ignorant see the person in the nonperson.

The sage sees the nonperson in the person.

Through pain and pleasure, joy and sorrow,

this is the one lesson we are learning.

In India we have learned that lesson

which no child can understand:

It is all vanity,

this hideous world is Maya. (From the Swami Vivekananda Vijnanagita)

What is being intimated in this part of our study of Yoga is this: what else are you going to do with the alambanas? Court them? Romance them? Invite them to assume reality? Try to possess them? Human beings have been doing all that for countless lifetimes and the sea of birth and death thus overflows continually. Now is the chance to inspect the principles of nature using your own honed and well-informed intelligence, simultaneously seeing them as components of the insentient principle of Prakriti and rendering them ineffective to bind you ever again. Use the method most suitable to you, but it must be done if you are dedicated to the tenets of Yoga. The result, a successful yogi or yogini, is a free soul, and it is not a coincidence that we do not see many of these here on this earth, for they have seen earth, known earth, and all the other visheshas, and have then and thereby swiftly commended their souls back to God after getting free of matter.